The Maya site of Colha, located in Northern Belize, is known for its lithic workshops. At its height, stone tools made at the site were traded with communities as far as 160 km (100 miles) away. The site is located geographically along a large seam of flint-like chert. The making of stone tools emerged initially as a cottage industry during the Middle Preclassic (1000-400 BC).

By the Late Preclassic (400 BC-AD 250), previously undeveloped swamps and hillsides were transformed into farmland yielding several crops a year. Population in Colha grew rapidly to accomodate the now large-scale lithic production carried out in workshops near the center of the site. Formal plazas, temples and a ball court at the site also date to the Late Preclassic.

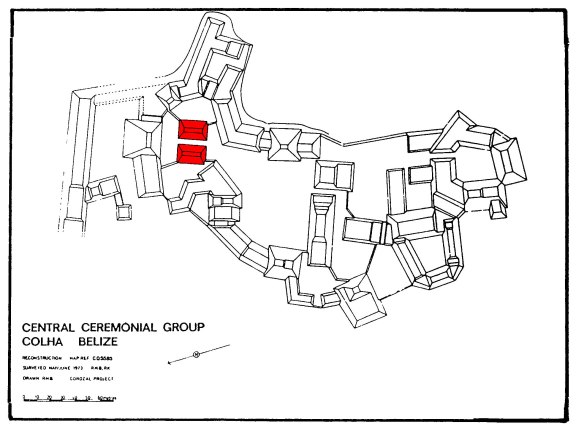

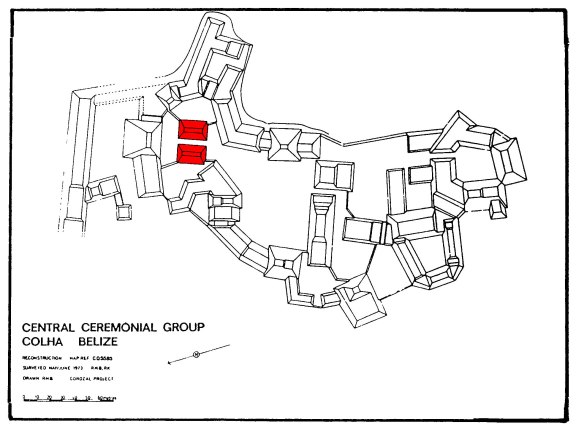

The ruins at Colha, Belize

Plan of the monumental center at Colha, Belize. The ball court is in red. (Corozal Project, 1973)

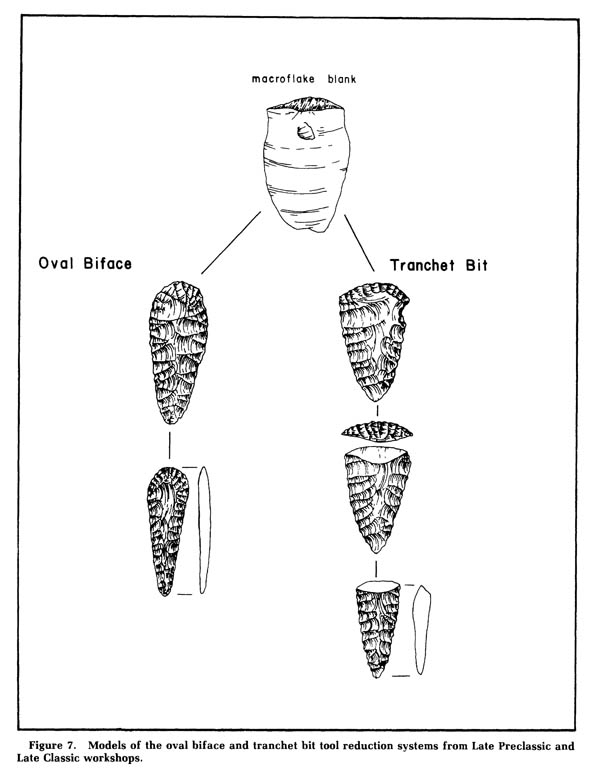

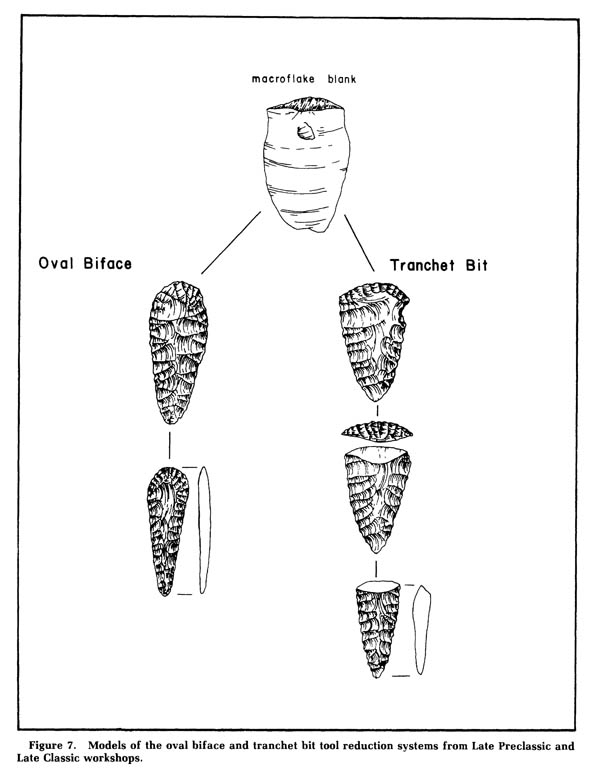

The Colha workshops produced a limited range of tools, which were likely used primarily for the clearing and working of land. The three utilitarian tools produced included large oval bifaces, tranchet bit implements, and long parallel-sided bifaces. A smaller number of microblades and biface eccentrics, which appear to have been used as prestige items by elites, were also made at Colha.

From “Ancient Chert Workshops in Northern Belize, Central America” by Harry J. Shafer and Thomas R. Hester. In American Antiquity, vol. 48, no. 3 (July, 1983), p. 528.

The technique of biface thinining used in making the tranchet adze, or axe, was unique to Colha and required a skilled hand. Blanks or cores produced in the chert quarries were transported to the workshops where craftsmen further shaped each tool. Interestingly, the bit end of each adze was formed by removing a large rounded “orange peel” flake through hard-hammered percussion. The orange peel flake itself is very distinctive in its smooth curved appearance.

TU1977.3.3 (8.5 cm), TU1977.3.4 (11 cm), TU1977.3.2 (11 cm)

Another view of orange peel flakes from Colha, Belize.

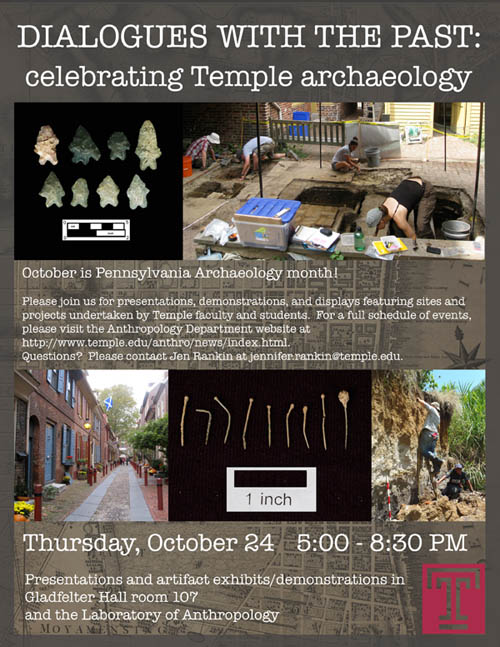

The Temple Anthropology Lab accessioned a surface collection of 64 pieces of lithic material from the workshop site of Colha, Belize in 1977. The artifacts were collected during a 1976 lithic conference at the site by Juliette Cartwright, a former Temple undergraduate student. Permission was granted for the donation by the Archaeological Commissioner of Belize for the purpose of adding to the lab’s comparative collection and increasing accessibility to those who wished to study them.

Sources:

Hammond, Norman. “Preclassic Maya Civilization”. In New Theories on Ancient Maya, edited by Elin C. Danien and Robert J. Sharer (Philadelphia: The University Museum, 1992)

Shafer, Harry J. and Thomas R. Hester. “Ancient Maya Chert Workshops in Northern Belize, Central America”. In American Antiquity, Vol. 48, No. 3 (Jul., 1983), pp. 519-543

Sharer, Robert J. and Loa P. Traxer. The Ancient Maya, 6th Edition (Stanford University Press, 2006)